Le TAS Rejette les recours du Stade Gabésien contre l’AS Kasserine et du CSSfaxien contre l’ESSahel. 10.6.2016

2016-06-11

La Rédaction De La Sentence Arbitrale

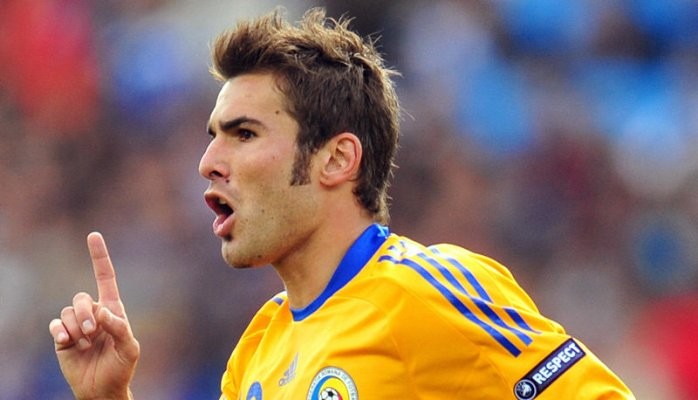

2016-06-16Les interminables ramifications de l’affaire Adrian Mutu

Adrian Mutu est l’un des plus grands talents du football roumain. S’il avait bien géré sa carrière, il aurait eu le même succès que le légendaire Georghe Hagi !

En 2003, Mutu a été transféré de Parma à Chelsea pour la faramineuse somme de 22,5 millions d’Euros. Huit mois par la suite, il a été contrôlé positif à la cocaïne, chose qu’il a reconnue par la suite. Après une suspension relativement longue, Mutu a pu rejouer pour Livorno puis pour la Juventus, puis encore pour la Fiorentina en Italie, à partir de juillet 2005.

Ayant subi une lourde suspension à cause de la cocaïne en 2004, Chelsea a mis fin à son contrat et l’a poursuivi en arbitrage pour faute lourde, lui réclamant de lui restituer la valeur de son transfert, au prorata temporis et de tous les frais occasionnés([1]). Etant donné qu’il a rendu ses services au profit de Chelsea pendant 8 mois, il a été condamné par le TAS à rembourser à Chelsea près de 18 millions d’Euros[2].

Le joueur a attaqué cette sentence devant le Tribunal Fédéral Suisse au motif qu’elle était confiscatoire et qu’elle portait ainsi atteinte à son droit de propriété, garanti par la Convention Européenne des Droits de l’Homme. Il a perdu cette manche, dans la mesure où le montant de l’indemnisation était proportionné à la valeur de son transfert[3].

Autrement, dit, s’il était évident que l’indemnisation était sans proportion avec l’indemnité de transfert et les émoluments touchés par ce joueur, il aurait été possible pour le Tribunal Fédéral d’annuler la sentence arbitrale du TAS.

Un recours a été formulé cette fois par le joueur contre la Suisse elle-même devant la CEDH, pour violation de son droit de propriété et de son droit à un procès équitable conformément à l’article 6 de la Convention de 1950, ainsi qu’à son droit au travail. L’action tend à voir condamner la Suisse (en tant qu’Etat de siège de l’arbitrage) à indemniser le joueur pour une condamnation prononcée par une institution d’arbitrage siégeant dans son territoire et sous le contrôle de ses juridictions publiques ! nous avons commenté cette décision à temps pour constater que le juge étatique doit donc annuler une sentence arbitrale pour injustice manifeste au cas où elle prononce des condamnations manifestement excessives et disproportionnées, et que ceci constitue l’une des limites au principe de la non-révision au fond des sentences arbitrales.

L’affaire est toujours pendante.

En 2010, Chelsea a attaqué les nouveaux clubs du joueur (Livorno et Juventus) au paiement des montants des condamnations prononcées contre le joueur. L’affaire a été enregistrée auprès de la DRC en Angleterre. L’action est fondée sur l’article 14.3 des Regulations governing the Application of the RSTP 2001, selon lequel « If a player is registered for a new club and has not paid a sum of compensation within the one month time limit referred to above, the new club shall be deemed jointly responsible for payment of the amount of compensation. »

Au 25 avril 2013, Chelsea a eu gain de cause sur la base de la règle de la solidarité entre le joueur et ses nouveaux employeurs.

La nouvelle sentence a été attaquée en appel devant le TAS en tant que juridiction arbitrale de second degré. L’affaire a été enregistrée sous les n°s 2013/A/3365 (Juventus) et CAS 2013/A/3366 (Livorono).

Par sa sentence unique du 21 janvier 2015, publiée sur la page officielle du TAS : http://www.tas-cas.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Award_3365-3366__internet_.pdf, le tribunal arbitral composé de Bernard Hanotiau President, Georg von Segesser et Jan Paulsson coarbitres, et avec l’assistance du secrétaire ad hoc du Tribunal arbitral Patrick Grandjean, le Tribunal arbitral TAS a rejeté les deux recours de la Juventus et de Livorno aux motifs ci-dessous. Avant de rapporter la motivation de la sentence, nous constatons que ce n’est pas la toute fin de ce feuilleton, car si la Juventus et Livorno payent des sommes à Chelsea, ils se retourneront contre Mutu pour se faire rembourses. Là, la question de la compétence sera plus épineuse, car Mutu n’est plus un joueur de football sera-t-il poursuivi devant un tribunal étatique ou devant le TAS ? Attendons les prochains épisodes

Les motifs de la sentence du TAS sont les suivants :

- MERITS 117. The following facts are undisputed: – The Player tested positive for cocaine in October 2004. – Following this adverse analytical finding, the employment relationship between Chelsea and the Player came to a premature end. – The Player did not engineer the contractual breach in order to be free to move to the club of his choice. – The Appellants did not induce the Player to breach his contract with Chelsea; nor were they implicated in any manner in the Player’s drug habits. – Livorno and, subsequently, Juventus registered the Player approximately three months after the end of his employment relationship with Chelsea. – The situation must be assessed in the light of Article 14.3. 118. On the basis of the above, the DRC found that the Appellants were jointly responsible, together with the Player, for the payment of the Awarded Compensation. For the reasons already exposed, the Parties cannot agree upon the scope of Article 14.3. In substance, the Appellants claim that Article 14.3 apply in cases where a player leaves a club with the intention of joining another one, whereas Chelsea is of the view that the Appellants’ liability stems simply from their status as the Player’s New Club. Both the Appellants and Chelsea rely on general principles of interpretation of Swiss law to support their positions. 119. In light of the foregoing, the Panel will address the following issues: (i) What does Article 14.3 actually say? (ii) What is the legal nature of Article 14.3 under Swiss law? (iii) The principles governing the interpretation of the bylaws of a legal entity. (iv) The literal interpretation of Article 14.3. (v) Other aids to interpretation. (i) What does Article 14.3 actually say? CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 28 120. Article 14.3 is part of the « Regulations governing the Application of the [RSTP]. » It falls under Chapter VI « Enforcement of compensation awards » and reads as follows: « 1. The party responsible for a breach of contract is obliged to pay the sum of compensation determined pursuant to Art. 42 of the FIFA Regulations for the Status and 34 Transfer of Players within one month of notification of the relevant decision of the Dispute Resolution Chamber. 2. If the party responsible for the breach has not paid the sum of compensation within one month, disciplinary measures may be imposed by the FIFA Players’ Status Committee, pursuant to Art. 34 of the FIFA Statutes. Appeals against these measures may be lodged to the Arbitration Tribunal for Football (TAF). 3. If a player is registered for a new club and has not paid a sum of compensation within the one month time limit referred to above, the new club shall be deemed jointly responsible for payment of the amount of compensation. 4. If the new club has not paid the sum of compensation within one month of having become jointly responsible with the player pursuant to the previous paragraph, disciplinary measures may be imposed by the FIFA Players’ Status Committee, pursuant to Art. 34 of the FIFA Statutes. Appeals against these measures may be lodged to the Arbitration Tribunal for Football (TAF). » (ii) What is the legal nature of Article 14.3 under Swiss law? Preliminary remarks 121. There is a need to clarify the nature of Article 14.3 as it is the indispensable prerequisite for the application of the appropriate method of interpretation: whether this provision must be interpreted according to the general rules of interpretation of contracts (i.e. the statements of the parties are to be interpreted as they could and should be understood on the basis of their wording, of the principle of good faith, of the context as well as under the overall circumstances – see SFT 133 III 61 at 2.2.1 p. 67; SFT 132 III 268 at 2.3.2 p. 274 et seq.; SFT 130 III 66 at 3.2 p. 71 et seq.; with references) or according to other principles, namely the methods of interpretation applicable to the interpretation of statutes and articles of by-laws of legal entities. 122. In addition, the determination of the nature of Article 14.3 will also condition the way it is viewed as a part of the relevant juridical framework. Its interpretation must be consistent with the applicable legislation, so that its implementation does not lead to an unlawful result. 123. It is undisputed that the situation must be assessed according to Swiss law (see Chapter V above). In their respective submissions, the Parties sought to establish the nature of the obligation allegedly owed by the Appellants exclusively by referring to Swiss law, the application of which was furthermore confirmed by their respective legal experts during the hearing. The Parties’ respective positions CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 29 124. According to Chelsea and under Swiss law, the Appellants’ obligation resulting from Article 14.3 is a form of guarantee under Article 111 CO or of joint responsibility under Article 143 CO. Article 111 CO, under the title « Guarantee of performance by third party », states that « A person who gives an undertaking to ensure that a third party performs an obligation is liable in damages for non-performance by said third party. » Article 143 CO, under the title « Joint and Several Obligations », provides that « (1) Debtors become jointly and severally liable for a debt by stating that each of them wishes to be individually liable for performance of the entire obligation. (2) Without such a statement of intent, debtors are joint and severally liable only in the cases specified by law. » 125. Chelsea asserts that the Appellants are bound by the applicable FIFA Regulations and that Article 14.3 is therefore directly applicable to them through Article 10 para. 4 lit. a) of the FIFA Statutes. According to its legal expert, Prof. von der Crone (first legal opinion, para. 80), « the conditional guarantee under Art. 14 (3) is based on the membership of the clubs in the FIFA system. Consequently the resulting obligation is of contractual nature. » He continues that « Swiss law establishes direct legal relationship between members in its statutes and that it can, by doing so, in analogy to a contract in favour of a third party create claims directly enforceable among members » (second legal opinion, para. 13). Prof. von der Crone invokes this statement of Prof. Hans Michael Riemer (Berner Kommentar, Band 1, Bern 1990, Art. 70 CC, N. 134, translated by Prof. von der Crone, second legal opinion, para. 29): « in analogy to a contract in favour of a third party (Art. 112 CO), duties of contribution of certain members of an association could be created so that other members have a direct claim. » 126. According to the Appellants, the guarantee under Article 111 CO or the assumption of debt based on Article 143 CO require a contractual agreement to this effect. They argue that the fact that the Parties are indirect members of FIFA does not create a contractual relationship between them. Assuming that there were contractual links between the Parties, both provisions require the constituent element of a contract to be met. In the present case, the debt to be assumed by the New Club is neither determined nor determinable (Prof. Besson, first legal opinion, para. 93) and Article 14.3 does not constitute an offer for, nor an acceptance of, nor a consent to a guarantee agreement or to an assumption of debt agreement between the Appellants and Chelsea (Prof. Probst, legal opinion, para. 50 and para. 57). If Chelsea’s contention were followed, it would mean that the Appellants promised a guarantee not only « to Chelsea but, by the same token, also to the several thousands of other clubs affiliated to one of the 209 FIFA members and that such a wide-spread promise was made for an unlimited amount but also for an unlimited duration » (Prof. Probst, legal opinion, para. 46). Such a guarantee would obviously go against the New Club’s personality rights as protected by Article 27 para. 2 of the Swiss Civil Code (hereinafter « CC »), according to which « No person may surrender his or her freedom or restrict the use of it to a degree which violates the law or public morals ». (Prof. Besson, first legal opinion, para. 90; Prof. Probst, legal opinion, para. 46). Rules of an association can be binding but it does not mean that they are contractual in nature (Prof. Besson, first legal opinion, para. 33). The Panel’s determination 127. The issue to be resolved is whether there is a contractual relationship between the former club and the New Club due to the mere fact that they are indirect members of CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 30 FIFA and that the New Club hired a player, a) who was dismissed with immediate effect by the former club and b) who had no intention to leave the latter. 128. The Parties’ legal experts agree that the obligations resulting from Articles 111 CO or 143 CO require the existence of a contract between the relevant Parties (Prof. Probst, legal opinion, para. 43 and para 54; Prof. Besson, first legal opinion, para. 92 et seq.; Prof. Besson, second legal opinion, para. 31 et seq.; Prof. von der Crone, first legal opinion, para. 80). It is also undisputed among the Parties that clubs must comply with the relevant FIFA regulations and that no direct or express contract has been concluded between Chelsea and the Appellants with respect to the Player. 129. One may become a member of an association either by participating in the founding meeting and approving the articles of association or, at a later stage, by being accepted via membership application (article 70 para. 1 CC; SFT 108 II 6). In the latter case, on the one hand, the applicant wishing to become a member must – at least implicitly – manifest its acceptance to be bound by the statutes of the association and, on the other hand, the association must – either formally or informally — accept its membership application. Becoming a member after the founding of the association implies the formation of a specific contractual relationship whereby the candidate expresses its intent to join the association and the association expresses its consent to the candidate’s application (Bénédict Foëx, in Pichonnaz / Foëx, Commentaire romand, Helbling & Lichtenhahn, Bâle, 2010, ad. art. 70, n 5, p. 511). This exchange of mutual and concordant assents constitutes a contract, the scope of which is limited to the acquisition of membership. As soon as the applicant acquires the status of member, it is no longer bound to the association by a contractual relationship, but by a specific relationship, associative in nature (ibidem). In this respect, the SFT has confirmed that, in the absence of contract between an indirect member of a federation and the federation itself, there is no contractual liability (SFT 121 III 350, consid. 6 a) and 6 b) hereinafter the « Grossen case »). 130. In the Grossen case, Mr René Grossen, an amateur wrestler, was an indirect member of the « Fédération Suisse de Lutte Amateur » (hereinafter « FSLA »). He fulfilled the requirements set by the FSLA to qualify for the World Wrestling Championships. As part of his preparation for this event, Mr Grossen incurred costs, consisting namely of unpaid holidays and training camps. Without any valid reason, FSLA changed the rules concerning the qualification to the World Wrestling Championships, with the result that Mr Grossen selection was reversed. The athlete lodged a claim against FSLA for payment of his expenditures. The SFT held that there was no contractual relationship between Mr Grossen and FSLA and had therefore to resolve whether Mr Grossen’s claim could rely on another source of obligations (« a) Faute d’un quelconque contrat liant les parties, une responsabilité contractuelle de la défenderesse n’entre pas en considération en l’espèce. b) Il convient de se demander en revanche si la responsabilité de la défenderesse n’est pas engagée sur la base de l’art. 41 CO. » SFT 121 III 350). It awarded Mr Grossen compensation on the ground that the FSLA had an enforceable duty to act in good faith vis-à-vis athletes. The compensation was awarded on account of breach of trust, as it was Mr Grossen’s legitimate expectation that the rules he complied with would be respected. 131. In view of the above, the Panel does not consider that there is a contractual relationship between the Appellants and Chelsea. If there is no contractual relationship between an indirect member (i.e. any of the Parties) and a sport federation (i.e. FIFA), the CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 31 conclusion should be the same as regards the relationship between two indirect members of the same federation. Bearing in mind that the Appellants and Chelsea have concluded no specific agreement with respect to the Player, the Panel does not see how Chelsea can claim a) that the Appellants have contractually agreed to provide to Chelsea an independent guarantee within the meaning of Article 111 CO or b) that they have contractually agreed to assume the Player’s debt within the meaning of Article 143 CO. Acceptance of general rules (such as FIFA Regulations) does not necessarily entail subjection to specific obligations when their scope must be determinable on the basis of minimum criteria. 132. Prof. von der Crone is of the view that any reference to the Grossen case is misconceived as neither Mr Grossen’s club nor the FSLA obliged « their members to respect the statutes and regulation of the [FSLA] ». According to him, Grossen is only relevant for matters related to claims based on the principles of culpa in contrahendo or venire contra factum proprium (Prof. von der Crone, second legal opinion, para. 42 et seq.). 133. Assuming however that there is a contractual relationship between the Parties, Chelsea encounters the following difficulties: – Articles 111 CO and 143 CO are contractual in nature. Both provisions require the constituent element of a contract to be met. Under Swiss law, the conclusion of a contract requires a mutual expression of intent by the parties (Article 1 CO). Where the parties have agreed on all the essential terms, it is presumed that the contract will be binding notwithstanding any reservation on secondary terms (Article 2 para. 1 CO). In other words, it is necessary for a valid contract to come into existence that the parties have agreed on the minimum content of their respective obligations. According to the SFT, the guaranteed debt must be sufficiently determinable at the moment of the conclusion of the contract. This derives from Articles 19 para. 2 CO and 27 para. 2 CC (SFT 120 II 35 consid. 3 a). The debt is sufficiently determinable when the creditor and the object of the claim can be identified. In this light, the commitment whereby the guarantor accepts to take responsibility for any future claims, regardless of their legal ground, is not acceptable (SFT 128 III 434, consid. 3 a). In a matter of contract of surety (Articles 492 et seq. CO), the SFT considered as null and void the clause whereby the guarantor consented in advance to any change in the person of the principal debtor. It held that the validity of the guarantee was subject to the condition that the guarantor must be in a position to see clearly the nature and the extent of the risk it was willing to assume (SFT 67 II 128 consid. 3). The Panel is of the opinion that Article 14.3 does not contain the basic terms or minimum content in order to be held effective against the New Club, which hired a player dismissed with immediate effect by his former employer. – The obligation under Article 111 CO is an abstract undertaking to pay a specified amount to the secured party upon the latter’s request. The payment of the guarantee (which is non-accessory to the third party’s debt) becomes due when the third party fails to perform its obligation. The cause of its failure is irrelevant (Pierre Tercier / CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 32 Pascal G. Favre, Les contrats spéciaux, 4th edition, Schulthess, 2009, page 1074, para. 7156 and references). Pursuant to Article 14.3, « the new club shall be deemed jointly responsible for payment of the amount of compensation. » The terms « jointly responsible » suggest that the debt of the guarantor is an accessory to the main debt, which is incompatible with Article 111 CO (Prof. Besson, second legal opinion, para. 45). In this respect, it seems obvious to the Panel that Chelsea’s claim against the Appellants is inseparably tied to Chelsea’s claim against the Player. Should the Player be, for any reason, released from his obligations towards Chelsea, it does not seem reasonable that Chelsea’s claim against the Appellants would survive. Following therefrom, and still assuming that a contractual relationship exists, (which is clearly not the view of the Panel), the relationship would have to be qualified as a contract of suretyship pursuant to Article 492 at seq. CO rather than a guarantee under Article 111 CO. Moreover, where it is not possible to clearly establish the parties’ intent with regard to the abstract undertaking, there is according to the SFT a presumption that the parties meant to be bound by a contract of surety (Articles 492 et seq. CO), the validity of which is subject to the respect of certain formal requirements (e.g. the indication of the maximum amount of the guarantor’s liability), which are not met in the present case. The Panel is accordingly of the opinion that Article 14.3 does not constitute a guarantee under Article 111 CO nor a suretyship under Article 492 CO. – Still assuming that there is a contractual relationship (quod non), Article 14.3 cannot establish an assumption of debt under Article 143 CO. The cumulative assumption of debt between the creditor and the debt acquirer, must meet the ordinary legal requirements for the conclusion of a valid contract pursuant to the rules of the Swiss Code of Obligations (see above and SFT 128 III 434). The wording of Article 14.3 is much too undetermined and not sufficiently determinable as it does not identify which specific claim of which creditor against which debtor is concerned by the alleged assumption of debt. As Prof. Probst rightly concluded in his opinion: « Swiss Law of Obligations does not endorse the concept of a contract with whom it may concern and on what object and amount it may be ». – With regard to Chelsea’s view that Article 14.3 provides for a strict liability, Prof. Probst pointed out that, per se, Article 14.3 in itself already imposes a very serious liability. This joint liability applies not only when there is inducement from the New Club but worse, when there is a presumption of inducement, such as would arise from the moment the player leaves his club without serious reason and is hired by the New Club. According to Prof. von der Crone, Article 14.3 does not contain any limitation and does not condition the new club’s joint and several liability on the New Club being proven to have induced the player’s breach or otherwise being at fault. CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 33 The award in case CAS 2007/A/1298, 1299 & 1300 (Webster case) rejected a contention by the new club to the effect that (para. 160) « it should not be held jointly liable on the basis of the foregoing provision because it took no part in inciting the Player to leave [his former club] and that it had not made him any offer or even made contact with him at the time he decided to leave [his former club]. » The Panel held that (para. 160 et seq.) « In light of the evidence on record, the Panel has no reason to doubt [the New Club’s] assertion in this respect or therefore to conclude that [the new club] had any causal role in the Player’s decision to terminate his contract with [his former club] (…). Consequently, the Panel considers that the joint and several liability provided under 17(2) must be deemed a form of strict liability, which is aimed at avoiding any debate and difficulties of proof regarding the possible involvement of the new club in a player’s decision to terminate his former contract, and as better guaranteeing the payment of whatever amount of compensation the player is required to pay to his former club on the basis of article 17. The Panel finds therefore that [the New Club] is jointly and severally liable with the Player for the payment of [the compensation following his breach of the contract without just cause] ». Prof. Probst and Prof. Besson expressed the view that by a parity of reasoning the New Club’s liability should not a contrario be applied lightly in cases, like the present one, where it is clear that there has not been inducement. It would otherwise be strikingly unfair to impose liability. Indeed, one can conceive that there can be in some cases a strict liability regime, i.e. liability without fault, but there is no example in the law of a liability without causation (in a non-contractual context, which is the case here); or even worse, liability when the New Club has had no role in the disruption of the prior employment. It is a fundamental principle under Swiss law that obligations do not arise in the absence of a valid cause (SFT 105 II 183 and Silvia Tevini, in Thévenoz / Werro, Commentaire romand, Helbling & Lichtenhahn, Bâle, 2012, ad. art. 17, n 2, p. 129 and numerous references). In the present case, it is Chelsea’s case that the valid cause at the origin of its contractual claim stems simply from the Appellants’ status as the Player’s New Club. As there is no contractual relationship between the Parties, Chelsea’s conclusion is untenable. 134. Based on the foregoing, the Panel comes to the conclusion that the alleged guarantee cannot arise solely by virtue of the Appellants’ indirect membership in the FIFA system, as claimed by Chelsea. Given that the statutes of an association are not bilateral contracts between the association and its members, there is not basis to conclude that the same statutes constitute a contractual relationship between indirect members of the same association. 135. This conclusion is consistent with a previous CAS Case 2009/A/1909, which concerned a player who had concluded two employment contracts, valid as from 1 July 2008. The first agreement was signed on 1 February 2008 with a Spanish club and the second with a Qatari club on 17 March 2008. The player decided to honour the first signed contract. The Qatari club initiated proceedings with FIFA to obtain compensation as a consequence of the breach of contract without just cause, and to hold the Spanish club jointly and severally liable for the payment of such compensation. In the appeal CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 34 proceedings before it, the CAS found that the player was indeed bound by the second contract (para. 37), which he breached without just cause (para. 40). It held that the Spanish club could not be held jointly and severally liable for the payment by the player of the damages awarded to the Qatari club, because its contract with the player had been signed before the contract signed with the Qatari club. « As a result, [the Spanish club], being already the club of the Player at the time of the breach, cannot be considered as the new club of the Player for the purposes of Article 17.2 of the Regulations » (para. 55). Moreover, the Spanish club raised a counterclaim against the Qatari club for the damages it incurred because of the latter’s conduct. The Panel dismissed the Spanish club’s counterclaim on the following grounds (para. 73): « Failing a contract between [the Spanish club] and [the Qatari club], [the Spanish club’s claim] intends to enforce an extra-contractual (or tort) liability of [the Qatari club], alleging a sort of interference of [the Qatari club] with the plain implementation of the first contract. The Panel, however, remarks that no legal basis for such claim has been specified by [the Spanish club], and, in any case, that no wrongful action appears to have been committed by [the Qatari club]: [the Qatari club] had a contract signed by the Player, even though a termination without just cause had been declared. [The Qatari club], therefore, was entitled to try to enforce the contractual obligations of the Player. By doing so, [the Qatari club] did not commit any wrongful action ». 136. In view of the above considerations, the Panel finds that the Appellants’ putative liability based on Article 14.3 is not contractual in nature. (iii) The principles governing the interpretation of the bylaws of a legal entity Introduction 137. At the hearing, the Parties’ respective experts accepted that, under Swiss law, the methods of interpretation to be applied are the following: – the literal interpretation (« interprétation littérale »); – the systematic interpretation (« interprétation systématique »); – the principle of purposive interpretation (« interprétation téléologique »); – the principle of so-called « compliant interpretation » (« interprétation conforme »). 138. They also agreed that, as a rule, although the starting point is the wording of the text to be interpreted there is no hierarchy among the methods listed above. Prof. Probst explained that Swiss law does not have the concept of « sens clair » and that the meaning of a word must also be supported by its purpose. Between the various rules of interpretation, there is a chronological order but not a logical one. Prof. von der Crone accepted the absence of hierarchy in the methods of interpretation but emphasised that the wording was of significant importance. 139. According to the SFT, the starting point for interpreting is indeed its wording (literal interpretation). There is no reason to depart from the plain text, unless there are objective reasons to think that it does not reflect the core meaning of the provision under review. This may result from the drafting history of the provision, from its purpose, or from the systematic interpretation of the law. Where the text is not entirely clear and there are several possible interpretations, the true scope of the provision will need to be CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 35 narrowed by taking into account all the pertinent factors, such as its relationship with other legal provisions and its context (systematic interpretation), the goal pursued, especially the protected interest (teleological interpretation), as well as the intent of the legislator as it is reflected, among others, from the drafting history of the piece of legislation in question (historical interpretation) (SFT 132 III 226 at 3.3.5 and references SFT 131 II 361 at 4.2). When called upon to interpret a law, the SFT adopts a pragmatic approach and follows a plurality of methods, without assigning any priority to the various means of interpretation (SFT 133 III 257 at 2.4; SFT 132 III 226 at 3.3.5). The interpretation of the bylaws of a legal entity 140. There is no unified view on how articles of associations should be interpreted in Switzerland (Holger Fleischer; die Auslegung von Gesellschaftsstatuten: Rechtsstand in der Schweiz und rechtsvergleichende Perspektiven; GesKR 4/2013, p. 8; Piermarco Zen-Rffinen, Droit du Sport, Schulthess 2002, p. 63). 141. The issue is whether the articles of associations should be interpreted by using the principles applied to the interpretation of contract or to the interpretation of statutory laws. As the articles of association form the contractual basis of an association – a private law institution – it can be argued that they have much in common with contracts and should therefore be interpreted through the contractual principles of the subjective intent of the parties and good faith (Forstmoser/Meier-Hayoz/Nobel, §7 N 4; Zeller, §11 N 129-133; Valloni/Pachmann, p. 25). However, articles of association also set forth constitutive principles which may have effects to others apart from the original members of the association, and should therefore be subject to the more objective approach followed with respect to statutory laws (Forstmoser/Meier-Hayoz/Nobel, §7 N 3). 142. Factors taken into account by Swiss scholars when deciding what method of interpretation should be used include the following: – The most important guiding principle for interpretation is the purpose; the purpose and the interests of the members take precedence over the intentions and interests of the founders (Articles of association should be interpreted in an objective way pursuant to the same principles applicable to the interpretation of statutes (Heini/Scherrer in Basel Commentary, 4th ed. N 22 to Art. 59 CC).. – The interpretation must take into consideration the fact that the articles of association are binding on future shareholders and therefore be construed from the point of view of persons who are not familiar with the origins and rely on the text itself (Fleischer, op. cit. p. 509, citing SFT 26 II 276). – The method of interpretation of articles of association of a corporation offering shares to the wider public should be similar to that applied to the interpretation of statutory law (Fleischer, op. cit. p. 509, citing SFT 107 II 179; 4C.386/2004, cons. 3.4.1). – The nature of the provision to be interpreted should be taken into account: principles of contract interpretation may commend themselves when the provision relates only to internal issues, whereas principles of statutory interpretation CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 36 become prominent when the provision concerns the interests of third parties. (Forstmoser/Meier-Hayoz/Nobel, §7 N 44-46). – Similarly, German courts differentiate between provisions with legal effects on individuals and those affecting the corporation as a whole (Fleischer, op. cit, p. 511). 143. According to the SFT, the statutes of a private legal entity are normally interpreted according to the principle of good faith, which is also applicable to contracts (SFT 4A_392/2008, at 4.2.1 and references). However, the method of interpretation may vary depending on the nature and dimension of the legal person involved. As regards the statutes of larger entities, it may be more appropriate to have recourse to the method of interpretation applicable to the law, whereas in the presence of smaller enterprises, the statutes may more legitimately be interpreted by reference to good faith. The subjective interpretation will be required only when a very little number of stakeholders are concerned (SFT 4A_235/2013, at 2.3 and 4C.350/2002, at 3.2). 144. FIFA is a very large legal entity with over not only two hundred affiliated associations, but also far more numerous indirect members who must also abide by FIFA’s applicable regulations (SFT 4P.240/2006). It is safe to say that FIFA’s regulations have effects which are felt worldwide, and should therefore be subject to the more objective interpretation principles. (iv) The literal interpretation of Article 14.3 145. According to Article 14.3, « the new club shall be deemed jointly responsible for payment of the amount of compensation ». 146. The Appellants infer from the words « shall be deemed » a rebuttable possibility and presumption, but not a certainty or automaticity (Prof. Besson, first legal opinion, para. 47). According to them, just as a New Club can rebut the presumption under Article 23 of the RSTP 2001 (pursuant to which it is presumed to have induced the breach of contract by the player and therefore must be sanctioned), a New Club can also escape joint liability by establishing that it was not involved in any manner in the termination of the Player’s employment agreement with his former employer (ibidem, para. 47 and Prof. Besson, second legal opinion, para. 21 et seq.). 147. Chelsea is of the view that the words « shall be deemed » rather indicates that the New Club is responsible in circumstances where the player has not paid the awarded compensation. In support of this allegation, Prof. von der Crone asserted that « According to Black’s Law Dictionary, the word ‘deemed’ is used whenever describing a joint and several liability and is in the context of the present case to be interpreted as a synonym for ‘is' » (first legal opinion, para. 27 and second legal opinion, para. 33 et seq). Chelsea submits that whether the New Club induced the player to breach his contract is a separate issue, and only relevant from a disciplinary point of view and does not concern the joint liability of the New Club for the Awarded Compensation, left unpaid by the Player. 148. In view of the Parties’ respective and conflicting positions, it follows that Article 14.3 is not as unambiguous as either the Appellants or Chelsea want the Panel to believe. Although “shall be deemed” may be reduced to “is”, that depends on whether the CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 37 conditions that require the deeming have been met – which is the central question of this case. Under these circumstances, it is necessary to look beyond the wording of this provision. (v) The other interpretation tools The contextual approach 149. The Panel agrees with Juventus’ contention that the context surrounding the implementation of the RSTP 2001 is of crucial importance in interpreting Article 14.3. Although the European Court of Justice (ECJ) delivered two judgments concerning the sports sector during the 1970s (Walrave and Koch v. Association Union Cycliste Internationale, case no. C-36/74, 12 December 1974 and Doña v. Montero, case no. C- 13-76, 14 July 1976), it was not until the 1990s that the European Union began to intervene significantly in sport, concomitantly with the realisation of its emergence as a globally significant economic activity. The ECJ’s judgment of 1995 concerning the Belgian footballer Jean-Marc Bosman inspired a series of complaints by sportsmen and women against sports organisations, whose decisions and/or rules were thus challenged in the European courts, resulting in restrictions on their autonomous regulatory power. The Bosman judgment ultimately caused FIFA to change its rules on transfers of players in 2001 (Jean-Loup Chappelet, Autonomy of sport in Europe, Sports policy and practice series, Council of Europe Publishing, February 2008, p. 25). 150. Bosman arose out of a dispute in 1990 between Mr Bosman and his club. Mr Bosman claimed that the transfer rules of the Belgian Football Federation and of UEFA-FIFA had prevented his engagement by a French club. In its decision, the ECJ held that the then-applicable transfer rules directly affected the players’ access to the employment market in other Member States and could thus impede the freedom of movement of workers (Case C-415/93, Bosman, European Court Reports, 1995, I-4921, 15 December 1995). According to the European Commission, the precise meaning of the Court’s decision was the following: « If a professional football player’s contract with his club expires and if that player is a citizen of one of the Member States of the European Union, this club cannot prevent the player from signing a new contract with another club in another Member State or making it more difficult, by asking this new club to pay a transfer, training or development fee » (CAS 2003/O/527, para. 7.2.3, page 8 and references). 151. As part of the reform of the FIFA and UEFA rules following the Bosman decision, FIFA adopted the RSTP 2001 after it « reached agreement with the European Commission on the main principles for the amendment of FIFA’s rules regarding international transfers. Thereupon, FIFA drafted amendments to its regulations on the status and transfer of players, taking into account these principles » (« FIFA Circular Letter n° 769 », page 1). 152. According to the Statement of the then Competition Commissioner Mario Monti of 5 June 2002 (IP/02/824) « FIFA has now adopted new rules which are agreed by FIFpro, the main players’ Union and which follow the principles acceptable to the Commission. The new rules find a balance between the players’ fundamental right to free movement and stability of contracts together with the legitimate objective of integrity of the sport and the stability of championships. It is now accepted that EU and national law applies to football, and it is also now understood that EU law is able to take into account the CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 38 specificity of sport, and in particular to recognise that sport performs a very important social, integrating and cultural function. Football now has the legal stability it needs to go forward ». 153. It is undisputed that one of the objectives of the FIFA regulations is to protect contractual stability, which is considered to be « of paramount importance in football, from the perspective of clubs, players, and the public » (« FIFA Circular Letter n° 769 », page 10). The potential conflict between rules governing contractual stability and players’ freedom of movement obviously provided the backdrop for FIFA regulations, which must strike a balance between the players’ rights and an efficient transfer system, responding to the specific needs of football and preserving the legitimacy and proper functioning of sporting competition. 154. In the case Jyri Lehtonen v FRBSB (C-176/96 of 13 April 2000), the ECJ found that rules on transfer periods can constitute an obstacle to freedom of movement for workers. However, it also held that such restrictions may be objectively justified. In particular, it observed that « the setting of deadlines for transfers of players may meet the objective of ensuring the regularity of sporting competitions. Late transfers might be liable to change substantially the sporting strength of one or other team in the course of the championship, thus calling into question the comparability of results between the teams taking part in that championship, and consequently the proper functioning of the championship as a whole. (…) The teams taking part in the play-offs for the title or for relegation could benefit from late transfers to strengthen their squads for the final stage of the championship, or even for a single decisive match. However, measures taken by sports federations with a view to ensuring the proper functioning of competitions may not go beyond what is necessary for achieving the aim pursued » (para. 42 to para. 56; emphasis added). 155. In other words, a certain stability of employment contracts is necessary for a working economy, which means that rules preventing a player from unilaterally terminating his contract for a given length of time, are acceptable. The question is how long such restriction on an employee’s right to free movement may be justified. 156. In the wake of Lehtonen, the European Commission stated that national legislation imposing obligations in the case of breach of contract does not infringe Community law, as long as it avoids a disproportionate restriction on free movement (Case IV/36.583 SETCA – FCTB/FIFA of 28 May 2002 – hereinafter « SETCA »). The Commission notably made the following assessments of specific measures (see para. 52): – unilateral termination of the player’s employment contract for just cause or sporting just cause is authorized; – apart from these two situations and in order to preserve the regularity and proper functioning of sporting competitions – which is a legitimate objective recognized by the ECJ in the Lehtonen case – unilateral breaches of contract are only possible at the end of a season; – to the same end, a player who breaches his contract during the first or the second year (or during the first year only, in the case of a player who signed his contract after he turned 28) may be suspended; – such a suspension cannot be longer than 4 months, unless there is recidivism or lack of notice, in which case the suspension may extend to 6 months; CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 39 – unilateral termination may result in financial compensation consistent with the applicable national law, designed to remedy and deter the breach of a contractual obligation. 157. Based on the foregoing, the Commission held that the limitations on unilateral termination introduced by the new FIFA Regulations would help improve the production and distribution of sport entertainment, since they would preserve the integrity of competitions. It stated that the prohibition of unilateral termination of contracts by players or by clubs during the season was essential to achieve the desired results. Should players be free to leave the competition at any given moment, the sporting value of the team during the championship would be significantly impaired, affecting and compromising the clubs and the smooth running of the championship as a whole (para. 56 of the award in SETCA). In the present case – contractual stability 158. It is undisputed that contractual stability is at the centre of the debate. 159. Chelsea claims that the rationale of Article 14.3 is not only to prevent poaching of players but also to ensure that the new club does not obtain a sporting or financial benefit from acquiring the player’s services for free while the original club is left uncompensated following the unjustified breach caused by the player. According to Chelsea, this provision is designed to protect contractual stability by means of a deterrent, namely by ensuring that the parties who benefit from the player’s breach – the player himself and his New Club – are not allowed to enjoy that benefit without paying compensation to the player’s former club. Chelsea considers that Article 14.3 compels the new club « to do the equivalent of what it would otherwise have to do if it wished to secure a player who was properly performing for the term of his playing contract. The compensation is a substitute for the transfer fee that any club has to pay if it wishes to secure a consensual early termination of a player’s contract with his club ». 160. According to the Appellants, Article 14.3 – and FIFA regulations in general – are not meant to protect a club’s bad investment. Their purpose « is to ensure contractual stability, i.e. to avoid players terminating their contracts without cause to move to another club; it is not to compensate a club that has decided to unilaterally terminate a player (for reasons that have nothing to do with the player’s intention to quit the club). » If Chelsea’s contention were followed, players in a situation similar to that of Mr Mutu would never find a new employer. 161. The Panel observes that none of the three cases of Bosman, Lehtonen, SETCA involved a contention that joint and several liability could be imposed upon a New Club which hired a player whose contract had already been terminated by his former employer. In this respect, the Panel notes that there is no doubt that the Player was in breach and fully responsible for the circumstances that justified the termination of his employment. That, however, obviously does not mean that he intended that his action would have those consequences, or that (more to the point) the Club did not have a choice in reacting to his breach. In simple terms: the Player was the author of his misfortune, but the Club was not required to terminate his employment if they still valued his services and preferred to hold him to his contract. The Club was entitled, not obliged, to dismiss him. That makes all the difference in terms of assessing the position of his subsequent employer(s) under the FIFA regulations, read in light of their object and purpose. CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 40 162. The present case seems one of the first impression. The findings of the ECJ and of the European Commission indicate that the new rules were intended a) to prevent late transfers which « might be liable to change substantially the sporting strength of one or other team in the course of the championship”, (Lehtonen para. 54) and b) to allow a club to build a successful unit and to work with players over a given length of time, without incurring the danger of losing them whenever they receive a better offer from another club (SETCA para. 57). Nor can it be inferred from the above cases that a player who committed an act of misconduct is in a similar position as the player who leaves his employer to join another club. In the present case, the Player tested positive for cocaine and Chelsea decided that the appropriate measure was to end his Employment Contract instead of resorting to other disciplinary measures without the radical financial impact implied by the termination. 163. In such a context, Chelsea’s proposed interpretation of Article 14.3 seems difficult to follow as it is Chelsea which chose to sack the Player and, as a consequence, to exclude him from its team. On 28 October 2004, when Chelsea put an end to the Player’s Employment Contract, no issue of contract stability, whose purpose was to safeguard the functioning and regularity of sporting competition, was at stake. As Chelsea took the decision to sever its relationship with the player, it strains logic for the club now to contend that the Appellants somehow enriched themselves by acquiring an asset (the player) which it chose to discard. 164. At the moment it terminated the Employment Contract with the Player, Chelsea’s claim was exclusively directed against the Player. Should the Player have never entered into a new employment contract, Chelsea would have never been compensated, given the plain unlikehood that the Player would never be able to pay the awarded amount (see Chelsea’s answer, paras. 6, 44.9 and 49.4). Under these circumstances, the Panel finds it hard to understand how, in the name of contract stability, Chelsea’s claim of EUR 17,173,990 against the Player is to be borne jointly and severally by the New Club, which has never expressed a specific agreement in this regard, had nothing to do with the Player’s contractual breach, and was not even called to participate in the proceedings, which established the Awarded Compensation. 165. With this in mind, Chelsea’s position seems all the more contradictory given that, when it fired the Player, it took the risk of bearing the damage resulting from the contractual breach. Chelsea now advances the inconsistent contention that the integrity of sport and the stability of championships would be endangered if the New Club could obtain a sporting or financial benefit from acquiring the Player’s services for free while the original club is left uncompensated. It seems incongruous for Chelsea to try to seek an advantage from the fact that the New Club benefits from the Player’s services, whereas Chelsea was no longer interested in his services. 166. If Chelsea had attributed some value to the Player, it would have looked into a possible transfer with another club willing to pay for the Player’s services. Obviously, Chelsea chose to follow another path: instead of negotiating the transfer of the Player, whose value was certainly affected by his drug habits and by the fact that Chelsea wanted to prematurely terminate his Employment Contract, Chelsea: a) decided to fire the Player, who was found to be responsible for the contractual breach on 20 April 2005, by decision of the FAPLAC, confirmed on 15 CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 41 December 2005 (CAS 2005/A/876 – Mutu v. FC Chelsea), i.e. more than two, and ten months, respectively, after the Player’s registration with the Appellants; b) obtained the confirmation of the Awarded Compensation against the Player, which acquired force of res judicata on 10 June 2010, (i.e. almost five years after the Player’s registration with the Appellants), following lengthy proceedings in which the Appellants were never called to appear; c) submitted a petition against the Appellants to the DRC, which held them jointly responsible, together with the Player, for the payment of the Awarded Compensation, with a decision notified on 7 October 2013. 167. The above circumstances call for the following comments: – In October 2013, more than eight years elapsed since the Appellants registered the Player. If contract stability, integrity of the sport, and the stability of championships had somehow been affected, Chelsea could have corroborated this contention with concrete evidence. It failed to do so. – For all the reasons already exposed, claims based on contract stability obviously require a certain level of immediacy. In the present case, Chelsea has not established in any manner that it had ever approached the Appellants before it initiated proceedings with the DRC on 15 July 2010. According to Chelsea, it was for the Appellants to get in touch with it in order to negotiate all the various terms relating to the acquisition of the Player’s services. However, Chelsea does not explain on what basis Livorno or Juventus were required to enter into communication with it, since when the Italian clubs registered the Player the latter was a free agent. Chelsea has never brought to the Appellants’ attention that they might be held jointly and severally liable for the Player’s contractual misconduct. There appeared to be even less reasons for the Appellants to inquire from Chelsea as to the Player’s potential liability and its effects, as they were never contacted in the course of several years and had never been called to participate in the proceedings initiated by Chelsea against the Player before the FAPLAC, FIFA, CAS or the SFT. 168. In these circumstances, Chelsea’s conduct appears to have had no other purpose than to increase its chances for greater financial compensation. Its position was particularly comfortable since, when it decided to initiate the proceedings against the Player, the Appellants had already registered him. Instead of immediately approaching Livorno or Juventus, it left them unaware of its ultimate intention until the Awarded Compensation acquired force of res judicata. The Panel does not see how Chelsea’s posture and strategy could be said to embody the pursuit of contractual stability. In particular, it does not see the connection between the damage being claimed and the interest of protecting legitimate contractual expectations. In the present case – the Player’s freedom of movement 169. There must be a balance between players’ fundamental right to free movement and the principle of stability of contracts, as supported by the legitimate objective of safeguarding the integrity of the sport and the stability of championships. 170. On the facts of this case, it appears unreasonable to assert – as Chelsea does – that, according to Article 14.3, joint liability could be imposed upon a New Club, even in the CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 42 absence a) of the New Club being proven to have induced the player’s breach or b) of the New Club otherwise being at fault, or irrespectively c) of the manner in which the player’s employment contract came to an end. It is undisputed that the joint and several liability for compensation (together with disciplinary sanctions if the requirements are met) will discourage any club from inducing a player to breach his contract with a former employer. However, such a deterrent effect has no purpose when a Player was dismissed by his former employer and is left with no other option but to find a new employer. If Chelsea’s interpretation were to be followed, it would mean that Article 14.3 would result in the imposition upon the New Club of an automatic and unconditional liability, without a finding of a fault or negligence and without a contractual basis – and hence without causation. Swiss law does not countenance such a result (SFT 105 II 183 and Silvia Tevini, op. cit. ad. art. 17, n 4, p. 129 and numerous references). 171. Chelsea’s response to the above findings is that no club is obliged to become the New Club. For Chelsea, it was Juventus’ independent choice to hire the Player, with the underlying obligation to contact Chelsea in order to negotiate all the various terms relating to the acquisition of the Player’s services. It is Chelsea’s position that « Each new club [whether it is responsible or not for the breach of the contract] must however, entirely reasonably, pay the price for the player (if he does not pay the compensation) set either by the club choosing simply to become a new club and assume the responsibility for what is awarded in the future, or by the club negotiating with the old club before becoming a new club. » 172. The Panel finds Chelsea’s interpretation of Article 14.3 untenable. If the New Club had to pay compensation even if it is established that it bears no responsibility whatsoever in the breach of the Employment Contract, the player would be hindered from finding a new employer. As a matter of fact, it is not difficult to perceive that no New Club would be prepared to pay a multi-million compensation (or transfer fee), in particular for a player who was fired for gross misconduct, was banned for several months, and suffered drug problems. 173. Chelsea claims that the amount to be paid by the New Club could be assessed through negotiation, just like a transfer fee. The two situations are not comparable: – In the present case, the Player was dismissed. If negotiations were to be carried out between his former employer and a potential New Club, the Player would not receive any salary, whereas in normal transfer negotiations, the player is bound to the club that is paying his salary. Chelsea’s comparison is unconvincing, as it would not have to pay the Player while conducting the negotiations with a potential new club. – In the present case, it is only in December 2005 that the Player was found to be responsible for the contractual breach, i.e. more than 10 months after his registration with the Appellants and more than a year after his dismissal by Chelsea. Until then, Chelsea’s claim against the Player was uncertain and so was its entitlement to request from the New Club the equivalent of a transfer fee. If Chelsea’s position were to be upheld, any negotiation would have to wait until a finding is made on whether the termination of the contract by the club was with or without just cause. During this period, no reasonable club would have taken the chance of hiring the Player. CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 43 – In the present case, it took almost five years for the Awarded Compensation to acquire force of res judicata (against the Player). Before the DRC, Chelsea claimed that its damage was to be determined on the basis of various factors, « including the wasted costs of acquiring the Player (£ 13,814,000), the cost of replacing the Player (£ 22,661,641), the unearned portion of signing bonus (£ 44,000) and other benefits received by the Player from the Club (£ 3,128,566.03) as well as from his new club, Juventus (unknown), the substantial legal costs that the Club has been forced to incur (£ 391,049.03) and the unquantifiable but undeniable cost in playing terms and in terms of the Club’s commercial brand values », but « at least equivalent to the replacement cost of £ 22,661,641. » The DRC awarded EUR 17,173,990, whereas CAS found that Chelsea was actually entitled to receive a greater amount, but, under the ultra petita principle, refrained from going beyond Chelsea’s request for relief (see CAS 2008/A/1644; para. 122, page 32). This confirms that the calculation of the compensation following the breach of contract without just cause is unforeseeable (See CAS 2008/A/1519-1520; para. 89 and Lucien W. Valloni and Beat Wicki, Compensation in case of breach of contract according to Swiss law, European Sports Law and Policy Bulletin, 1/2011, p. 159). In other words, a New Club would have to take the chance of hiring the Player and accept to be liable for the payment of an amount which is not determinable in advance. This is even more true as the New Club does not have information needed to assess such amount (namely the objective criteria, such as the salary and other benefits to which the player was entitled according to the old contract, the fees and expenses paid by the former club that were amortised over the duration of the contract, and the like). – In the present case, Chelsea was not under time pressure to conclude a deal with a New Club. It is hardly imaginable that Chelsea would claim GBP 22,661,641 before the DRC and, simultaneously, would be ready to settle with a New Club for a substantially lower amount. – The higher the compensation claimed the less chances for the Player to find a New Club with sufficient financial resources to consider the possibility of obtaining his services. This will also diminish considerably the Player’s chances to find a new employer. 174. It results from the above, that as long as no New Club would reach an agreement with the old club, the player would simply not be able to work and make his living. Chelsea’s interpretation of Article 14.3 would bring the matter back into pre-Bosman times, when transfer fees obstructed the players’ freedom of movement. In Bosman, it was found that « rules are likely to restrict the freedom of movement of players who wish to pursue their activity in another Member State by preventing or deterring them from leaving the clubs to which they belong even after the expiry of their contracts of employment with those clubs. Since they provide that a professional footballer may not pursue his activity with a new club established in another Member State unless it has paid his former club a transfer fee agreed upon between the two clubs or determined in accordance with the regulations of the sporting associations, the said rules constitute an obstacle to freedom of movement for workers. »(para. 99 and 100). It can be observed here that the SFT was mindful of Bosman as well as of the Player’s freedom of movement when it decided to confirm the Awarded Compensation (« This case is different from the matters which gave rise to the two precedents quoted [i.e. Bosman case and SFT 102 II 211], to the extent that the employees’ freedom of movement, invoked by [Mr Mutu], was not hindered at CAS 2013/A/3365 Juventus FC v. Chelsea FC CAS 2013/A/3366 A.S. Livorno Calcio S.p.A. v. Chelsea FC – Page 44 the end of the employment contract since after his suspension the player found a new employer in Italy, his immediate termination notwithstanding, without the new club having to pay a transfer fee to the [Chelsea] » (SFT 4A_458/2009, at 4.4.3.1). (vi) Conclusion 175. Chelsea’s interpretation of Article 14.3 is overly broad. It goes beyond the objective of protecting contractual stability. If Chelsea’s interpretation were accepted, the balance sought by the 2001 RSTP between the players’ rights and an efficient transfer system, which responds to the specific needs of football and preserves the regularity and proper functioning of sporting competition would be upset. It is incompatible with the fundamental principle of freedom to exercise a professional activity and is disproportionate to the protection of the old club’s legitimate interests. For the reasons already exposed, if Chelsea’s position were to be upheld, new clubs would be put off employing players carrying a compensation obligation. These players would then end up being permanently deprived of any source of professional revenue. 176. The obvious complication, which would arise if a potential New Club were to absorb the damages possibly assessed against a player sacked because of his misconduct, is considerable. The New Club might face the prospect of having to wait for a long time before knowing the amount due. This would likely have the consequence of freezing the player’s prospect on the job market. These effects are so obvious and significant that the failure to regulate them indicates that the author of Article 14.3 did not conceive that the text would apply to a player who had not wanted to leave the old club. 177. On the basis of the above considerations, the Panel finds that Article 14.3 does not apply in cases where it was the employer’s decision to dismiss with immediate effect a player who, in turn, had no intention to leave the club in order to sign with another club and where the New Club has not committed any fault and/or was not involved in the termination of the employment relationship between the old club and the Player. These findings do not compromise contractual stability, as a player will still be dissuaded from unilaterally breaching his contract (in some other way than terminating it), because he will then face the burden of a potential compensation awarded in favour of his previous club. The prospect of having to pay a high compensation may actually serve as a broader deterrent for players willing to put an end to their employment contracts than if a New Club were to be found jointly and severally liable. 178. Consequently, the Panel decides that the Decision under Appeal must be set aside. 179. The above conclusion makes it unnecessary for the Panel to consider the other requests and submissions presented by the Parties. Accordingly, all other prayers for relief are rejected.

[1] Le 6 Août 2007 et suite à la sentence du TAS-CAS n° 2006 / A / 1192, Chelsea a déposé auprès de la RDC une « demande Re- modifiée pour l’octroi d’une indemnisation» , en dommages-intérêts , à déterminer sur la base de divers éléments, « y compris les coûts d’acquisition et impenses perdues (13.814.000 £), le coût de remplacement du joueur (22.661.641 £) , le manque à gagner, une partie de prime à la signature (44.000 £) et d’autres avantages reçus par le joueur du Club (3,128,566.03 £), ainsi que de son nouveau club, la Juventus (inconnu), les intérêts et les frais juridiques que le Club a été contraint d’engager (391,049.03 £) et l’inquantifiable mais indéniable dommage causé à l’image de marque commerciale du Club » , « au moins équivalent au coût de remplacement de 22.661.641 £ » .

([2]) Sentence du TAS n°2008/A/1644, du 31 juillet 2009.

([3]) Request for annulment dated 14 September 2009.

Ahmed Ouerfelli

Avocat, arbitre